Japanese battleship Yamashiro

|

|

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Yamashiro |

| Namesake: | Yamashiro Province |

| Builder: | Yokosuka Naval Arsenal |

| Laid down: | 20 November 1913 |

| Launched: | 3 November 1915 |

| Commissioned: | 31 March 1917 |

| Struck: | 31 August 1945 |

| Fate: | Sunk during the Battle of Surigao Strait, 25 October 1944 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type: | Fusō-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 28.7 meters (94 ft 2 in) |

| Draft: | 8.7 meters (28 ft 7 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph) |

| Range: | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Complement: | 1,193 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

| General characteristics (1944) | |

| Displacement: | 34,700 long tons (35,300 t) |

| Length: | 212.75 m (698.0 ft) (o.a.) |

| Beam: | 33.1 m (108 ft 7 in) |

| Draft: | 9.69 meters (31 ft 9 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 4 × steam turbines |

| Speed: | 24.5 knots (45.4 km/h; 28.2 mph) |

| Range: | 11,800 nmi (21,900 km; 13,600 mi) at 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) |

| Complement: | approximately 1,900 |

| Sensors and processing systems: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | Deck: 152–51 mm (6–2 in) |

| Aircraft carried: | 3 × floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities: | 1 × catapult |

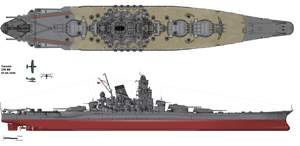

Yamashiro (山城, “Mountain castle”, named for Yamashiro Province) was the second of two Fusō-class dreadnought battleshipsbuilt for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Launched in 1915 and commissioned in 1917, she initially patrolled off the coast of China, playing no part in World War I. In 1923, she assisted survivors of the Great Kantō earthquake.

Yamashiro was modernized between 1930 and 1935, with improvements to her armor and machinery and a rebuilt superstructure in the pagoda mast style. Nevertheless, with only 14-inch guns, she was outclassed by other Japanese battleships at the beginning of World War II, and played auxiliary roles for most of the war.

By 1944, though, she was forced into front-line duty, serving as the flagship of Vice-Admiral Shōji Nishimura‘s Southern Force at the Battle of Surigao Strait, the southernmost action of the Battle of Leyte Gulf. During fierce night fighting in the early hours of 25 October against a superior American force, Yamashiro was sunk by torpedoes and naval gunfire. Nishimura went down with his ship, and only 10 crewmembers survived.

Contents

Description

The ship had a length of 192.024 meters (630.00 ft) between perpendiculars and 202.7 meters (665 ft) overall. She had a beamof 28.7 meters (94 ft 2 in) and a draft of 8.7 meters (29 ft).[1] Yamashiro displaced 29,326 long tons (29,797 t) at standard loadand 35,900 long tons (36,500 t) at full load. Her crew consisted of 1,198 officers and enlisted men in 1915 and about 1,400 in 1935.[2]

During the ship’s modernization during 1930–35, her forward superstructure was enlarged with multiple platforms added to her tripod foremast. Her rear superstructure was rebuilt to accommodate mounts for 127-millimeter (5.0 in) anti-aircraft (AA) guns and additional fire-control directors. Yamashiro was also given torpedo bulges to improve her underwater protection and to compensate for the weight of the additional armor. In addition, her stern was lengthened by 7.62 meters (25.0 ft). These changes increased her overall length to 212.75 m (698.0 ft), her beam to 33.1 m (108 ft 7 in) and her draft to 9.69 meters (31 ft 9 in). Her displacement increased nearly 4,000 long tons (4,100 t) to 39,154 long tons (39,782 t) at deep load.[2]

Propulsion

The ship had two sets of Brown-Curtis direct-drive steam turbines, each of which drove two propeller shafts. The turbines were designed to produce a total of 40,000 shaft horsepower (30,000 kW), using steam provided by 24 Miyahara-type water-tube boilers, each of which consumed a mixture of coal and oil. Yamashiro had a stowage capacity of 4,000 long tons (4,100 t) of coal and 1,000 long tons (1,000 t) of fuel oil,[3] giving her a range of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a speed of 14 knots(26 km/h; 16 mph). The ship exceeded her designed speed of 22.5 knots (41.7 km/h; 25.9 mph) during her sea trials, reaching 23.3 knots (43.2 km/h; 26.8 mph) at 47,730 shp (35,590 kW).[4]

During her modernization, the Miyahara boilers were replaced by six new Kanpon oil-fired boilers fitted in the former aft boiler room, and the forward funnel was removed. The Brown-Curtis turbines were replaced by four geared Kanpon turbines with a designed output of 75,000 shp (56,000 kW). On her trials, Yamashiro‘s sister ship Fusō reached a top speed of 24.7 knots (45.7 km/h; 28.4 mph) from 76,889 shp (57,336 kW).[1] The fuel storage of the ship was increased to a total of 5,100 long tons (5,200 t) of fuel oil that gave her a range of 11,800 nautical miles (21,900 km; 13,600 mi) at a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).[3]

Armament

The twelve 45-calibre 14-inch guns of Yamashiro were mounted in six twin-gun turrets, numbered one through six from front to rear, each with an elevation range of −5 to +30 degrees.[5] The turrets were arranged in an unorthodox 2-1-1-2 style with superfiring pairs of turrets fore and aft; the middle turrets were not superfiring, and had a funnel between them. The main guns and their turrets were modernized during the ship’s 1930 reconstruction; the maximum elevation of the main guns was increased to +43 degrees, increasing their maximum range from 25,420 to 32,420 metres (27,800 to 35,450 yd). Initially, the guns could fire at a rate of 1.5 rounds per minute, and this was also improved during her first modernization.[5]

Originally, Yamashiro was fitted with a secondary armament of sixteen 50-caliber 6-inch guns mounted in casemates on the upper sides of the hull. Each gun could fire a high-explosive projectile to a maximum range of 22,970 yards (21,000 m)[6] at up to six shots per minute.[7] She was later fitted with six high-angle 40-caliber three-inch AA guns, in single mounts on both sides of the forward superstructure and both sides of the second funnel, as well as on both sides of the aft superstructure.[1] These guns had a maximum elevation of +75 degrees, and could fire a 5.99-kilogram (13.2 lb) shell at a rate of 13 to 20 rounds per minute to a maximum height of 7,200 meters (23,600 ft).[8] The ship was also fitted with six submerged 533-millimeter (21.0 in) torpedo tubes, three on each broadside.[9]

Yamashiro and the aircraft carrier Kaga in Kobe Bay, October 1930

During Yamashiro‘s modernization in the early 1930s, all six three-inch guns were removed and replaced with eight 40-caliber 127-millimeter dual-purpose guns, fitted on both sides of the fore and aft superstructures in four twin-gun mounts.[10] When firing at surface targets, the guns had a range of 14,700 meters (16,100 yd); they had a maximum ceiling of 9,440 meters (30,970 ft) at their maximum elevation of +90 degrees. Their maximum rate of fire was 14 rounds a minute, but their sustained rate of fire was around eight rounds per minute.[11]

The improvements made during the reconstruction increased Yamashiro‘s draft by 1 meter (3 ft 3 in); the two foremost six-inch guns were removed, as the same guns on her sister ship Fusō had gotten soaked in high seas after that ship’s reconstruction. The ship’s light-AA armament was augmented by eight 25 mm Type 96 light AA guns in twin-gun mounts. Four of these mounts were fitted on the forward superstructure, one on each side of the funnel and two on the rear superstructure.[9] This was the standard Japanese light-AA gun during World War II, but it suffered from severe design shortcomings that rendered it a largely ineffective weapon. According to historian Mark Stille, the twin and triple mounts “lacked sufficient speed in train or elevation; the gun sights were unable to handle fast targets; the gun exhibited excessive vibration; the magazine was too small, and, finally, the gun produced excessive muzzle blast”.[12] The configuration of the AA guns varied significantly over time; in 1943, 17 single and two twin-mounts were added for a total of 37.[13] In July 1944, the ship was fitted with another 17 single, 15 twin and eight triple-mounts, for a total of 92 anti-aircraft guns in her final configuration.[14] The 25-millimeter (0.98 in) gun had an effective range of 1,500–3,000 meters (1,600–3,300 yd), and an effective ceiling of 5,500 meters (18,000 ft) at an elevation of 85 degrees. The maximum effective rate of fire was only between 110 and 120 rounds per minute because of the frequent need to change the fifteen-round magazines.[15]

Also in July 1944, the ship was provided with three twin-gun and 10 single mounts for the license-built 13.2 mm Hotchkiss machine gun.[14] The maximum range of these guns was 6,500 meters (7,100 yd), but the effective range against aircraft was only 1,000 meters (1,100 yd). The cyclic rate was adjustable between 425 and 475 rounds per minute, but the need to change 30-round magazines reduced the effective rate to 250 rounds per minute.[16]

Armor

The ship’s waterline armor belt was 229 to 305 millimeters (9 to 12 in) thick; below it was a strake of 102 mm (4 in) armor. The deck armor ranged in thickness from 32 to 51 mm (1.3 to 2.0 in). The turrets were protected with an armor thickness of 279.4 mm (11.0 in) on the face, 228.6 mm (9.0 in) on the sides, and 114.5 mm (4.51 in) on the roof. The barbettes of the turrets were protected by armor 305 mm thick, while the casemates of the 152 mm guns were protected by 152 mm armor plates. The sides of the conning tower were 351 millimeters (13.8 in) thick. Additionally, the vessel contained 737 watertight compartments (574 underneath the armor deck, 163 above) to preserve buoyancy in the event of battle damage.[17]

During her first reconstruction Yamashiro‘s armor was substantially upgraded. The deck armor was increased to a maximum thickness of 114 mm (4.5 in). A longitudinal bulkhead of 76 mm (3.0 in) of high-tensile steel was added to improve the underwater protection.[18]

Aircraft[edit]

Yamashiro was briefly fitted with an aircraft flying-off platform on Turret No. 2 in 1922. She successfully launched Gloster Sparrowhawk and Sopwith Camel fighters from it, the first Japanese ship to do so. During her modernization in the 1930s, a catapult and a collapsible cranewere fitted on the stern, and the ship was equipped to operate three floatplanes, although no hangar was provided. The initial Nakajima E4N2 biplanes were replaced by Nakajima E8N2 biplanes in 1938 and then by Mitsubishi F1M biplanes, from 1942 on.[19]

Fire control and sensors

The ship was originally fitted with two 3.5-meter (11 ft 6 in) and two 1.5-meter (4 ft 11 in) rangefinders in her forward superstructure, a 4.5-meter (14 ft 9 in) rangefinder on the roof of Turret No. 2, and 4.5-meter rangefinders in Turrets 3, 4, and 5.[20]

While in drydock in July 1943, a Type 21 air search radar was installed on the roof of the 10-meter rangefinder at the top of the pagoda mast. In August 1944, two Type 22 surface search radar units were installed on the pagoda mast and two Type 13 early warning radar units were fitted on her mainmast.[14]

Construction and service

Yamashiro testing her torpedo netsat Yokosuka in 1917

Yamashiro, named for Yamashiro Province, the former province of Kyoto,[21] was laid down at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal on 20 November 1913 and launched on 3 November 1915. She was completed on 31 March 1917 with Captain Suketomo Nakajima in command,[14] and was assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Fleet in 1917–1918. She did not take part in any combat during World War I, as there were no longer any forces of the Central Powers in East Asia by the time she was completed,[22] but she did patrol off the coast of China briefly during the war. On 29 March 1922, a Gloster Sparrowhawk fighter successfully took off from the ship. She aided survivors of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake in September 1923. Little detailed information is available about Yamashiro‘s activities during the 1920s, although she did make a port visit to Ryojun Guard District, in Manchuria, on 5 April 1925 and also conducted training off the coast of China.[14]

The ship’s reconstruction began on 18 December 1930 at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal where her machinery was replaced, her armor was reinforced, and torpedo bulges were fitted. Yamashiro‘s armament was also upgraded and her torpedo tubes were removed. Captain Chuichi Nagumo assumed command of the ship on 15 November 1934, her modernization was completed on 30 March 1935, and she became flagship of the Combined Fleet. Captain Masakichi Okuma relieved Nagumo on 15 November and he, in turn, was replaced by Captain Masami Kobayashi on 1 December 1936. Yamashiro began a lengthy refit on 27 June 1937 and Captain Kasuke Abe assumed command on 20 October. Her refit was completed on 31 March 1938 and Captain Kakuji Kakutarelieved Abe on 15 November. In early 1941, the ship experimentally launched radio-controlled Kawanishi E7K2 floatplanes. Captain Chozaemon Obata assumed command on 24 May 1941 and Yamashiro was assigned to the 1st Fleet’s 2nd Division,[Note 1] consisting of the two Fusō-class and the two Ise-class battleships.[14]

World War II

Yamashiro and her sister ship Fusō spent most of the war around Japan, mostly at the anchorage at Hashirajima in Hiroshima Bay.[13] When the war started for Japan on 8 December,[Note 2] the division, reinforced by the battleships Nagato and Mutsu and the light carrier Hōshō, sortied from Hashirajima to the Bonin Islands as distant support for the 1st Air Fleet attacking Pearl Harbor, and returned six days later.[14] On 18 April 1942, Yamashiro chased the Doolittle Raider force that had just launched an air raid on Tokyo, but returned four days later without having made contact.[23] On 28 May, she set sail, commanded by Captain Gunji Kogure, with the rest of the 2nd Battleship Division and the Aleutian Support Group at the same time that most of the Imperial Fleet began an attack on Midway Island (Operation MI).[24][25] Commanded by Vice-Admiral Shirō Takasu, the division was composed of Japan’s four oldest battleships, including Yamashiro, accompanied by two light cruisers, 12 destroyers, and two oilers. Official records do not show the squadron as part of the larger Midway operation, known as Operation AL; they were to accompany the fleet under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, but were only to provide support to the Aleutian task force if needed.[26] They were not needed, and Yamashiro returned to home waters where she was employed mostly for training duties, in the Inland Sea till 1 February 1943 and at Yokosuka until September, when she became a training ship for midshipmen.[13][23]

In an effort to replace the aircraft carriers lost at the Battle of Midway, the Navy made plans to convert the two Fusō-class ships to hybrid battleship/carriers, but the two Ise-class battleships were chosen instead. In July 1943, Yamashiro was at the Yokosuka drydock for fitting of a radar and additional 25 mm AA guns. The ship was briefly assigned as a training ship on 15 September before loading troops on 13 October bound for Truk Naval Base, arriving with the battleship Ise on the 20th. The two battleships sailed for Japan, accompanied by the carriers Jun’yō and Unyō, on 31 October.[14] On 8 November, the submarine USS Halibut fired torpedoes at Jun’yo that missed, but hit Yamashiro with a torpedo that failed to detonate.[27] Yamashiro resumed her training duties in Japan, and Captain Yoshioki Tawara assumed command. He was promoted to Rear Admiral on 1 May, but died of natural causes four days later,[14] and Captain Katsukiyo Shinoda was appointed to replace him.[28]

During the US invasion of Saipan in June 1944, Japanese troop ships attempting to reinforce the defenses were sunk by submarines. Shigenori Kami, chief of operations of the Navy Staff, volunteered to command Yamashiro to carry troops and equipment to Saipan. If the ship actually reached the island, he intended to deliberately beach the ship before it could be sunk and to use its artillery to defend the island. After Ryūnosuke Kusaka, Chief of Staff of the Combined Fleet, also volunteered to go, Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō approved the plan, known as Operation Y-GO, but the operation was cancelled after the decisive defeat in the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19 and 20 June.[29]

The ship was refitted in July at Yokosuka, where additional radar systems and light AA guns were fitted. Yamashiro and her sister ship were transferred to Battleship Division 2 of the 2nd Fleet on 10 September. The ship briefly became the division’s flagship under Vice Admiral Shōji Nishimura until 23 September when he transferred his flag to Fusō. They departed Kure on 23 September for Lingga Island, carrying the Army’s 25th Independent Mixed Regiment, and escaped an attack by the submarine Plaice the next day. They arrived on 4 October, where Nishimura transferred his flag back to Yamashiro. The ships then transferred to Brunei to offload their toops and refuel in preparation for Operation Shō-Gō, the attempt to destroy the American fleet conducting the invasion of Luzon.[14]

Battle of Surigao Strait

As flagship of Nishimura’s Southern Force, Yamashiro left Brunei at 15:30 on 22 October 1944, heading east into the Sulu Sea and then to the northeast into the Mindanao Sea. Intending to join Vice-Admiral Takeo Kurita‘s force in Leyte Gulf, they passed west of Mindanao Island into Surigao Strait, where they met a large force of battleships and cruisers lying in wait. The Battle of Surigao Strait would become the southernmost action in the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[30]

At 09:08 on 24 October, Yamashiro, Fusō and the heavy cruiser Mogami were spotted by a group of 27 planes, including Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers and Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bombers escorted by Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, coming from the carrier Enterprise.[31] Around 20 sailors on Yamashiro were killed by strafing and rocket attacks, and the ship listed by almost 15 degrees after a bomb’s near miss damaged the hull and flooded the starboard bilge, until counter-flooding in the port bilge righted the ship.[32]

Nishimura issued a telegram to Admiral Soemu Toyoda at 20:13: “It is my plan to charge into Leyte Gulf to [reach] a point off Dulag at 04:00 hours on the 25th.”[33] At 22:52, his force opened fire, damaging PT 130 and PT 152 and forcing them to retreat before they could launch their torpedoes.[34] Three American destroyers launched torpedoes at 03:00 that morning, hitting Fusō at 03:08 and forcing her to fall out of formation. Yamashiro opened fire with her secondary battery seven minutes later.[35] Around 03:11, the destroyers Monssenand Killen fired their torpedoes, one or two of which hit Yamashiro amidships. The resulting damage temporarily slowed the ship down, gave her a list to port and forced the flooding of the magazines for the two aft turrets. Yamashiro may have been hit a third time near the bow at 03:40.[36]

At 03:52, the battleship was attacked by a large formation to the north commanded by Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf. First came 6- and 8-inch (200 mm) shells from three heavy cruisers, Louisville, Portland, and Minneapolis, and four light cruisers, Denver, Columbia, Phoenix and Boise.[37] Six battleships formed a battle line; the Pearl Harbor veteran West Virginia was the first to open fire a minute later, scoring at least one hit with 16-inch (410 mm) shells in the first 20,800-meter (22,700 yd) salvo,[38] followed by Tennessee and California. Hampered by older radar equipment, Maryland joined the fight late, Pennsylvania never fired,[39] and Mississippi managed to fire exactly one salvo—the last of the engagement. The Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Shropshire also had radar problems and did not begin firing until 03:56.[40]

The main bombardment lasted 18 minutes, and Yamashiro was the only target for seven of them.[41] The first rounds hit the forecastle and pagoda mast, and soon the entire battleship appeared to be ablaze. Yamashiro‘s two forward turrets targeted her assailants, and the secondary armament targeted the American destroyers plaguing Mogami and the destroyer Asagumo.[42] The ship continued firing in all directions, but was not able to target the battleships with the other four operable 14-inch guns of her amidships turrets until almost 04:00, after turning west.[43] There was a big explosion at 04:04, possibly from one of the middle turrets. Yamashiro increased her firing rate between 04:03 and 04:09, despite the widespread fires and damage, and was hit during this time near the starboard engine room by a torpedo. By 04:09, her speed was back up to 12 knots, and Nishimura wired to Kurita: “We proceed till totally annihilated. I have definitely accomplished my mission as pre-arranged. Please rest assured.”[44] At the same time, Oldendorf issued a brief cease-fire order to the entire formation after hearing that the destroyer Albert W. Grant was taking friendly fire, and the Japanese ships also ceased fire.[45]

Yamashiro increased speed to 15 knots in an attempt to escape the trap,[45] but she had already been hit by two to four torpedoes, and after two more torpedo hits near the starboard engine room, she was listing 45 degrees to port. Shinoda gave the command to abandon ship, but neither he nor Nishimura made any attempt to leave the conning tower as the ship capsized within five minutes and quickly sank, stern first, vanishing from radar between 04:19 and 04:21.[46] Only 10 crewmembers of the estimated 1,636 officers and crew on board survived.[47]

Wreck

John Bennett claimed to have discovered Yamashiro‘s wreck in April 2001, but confirmation of the wreck’s identity could not be made.[48] On 26 November 2017, Paul Allen and his crew aboard the research ship R/V Petrel, discovered the wreck of Yamashiro and confirmed her identity. The ship was found upside down and mostly intact, with the forward bow folded over the hull and the area around the engine rooms partially collapsed.